Question: A good account manager always responds as quickly as possible to a client or internal request. Right?

Answer: Usually, but not necessarily.

Built into that responsiveness is the assumption that what the client or internal person wants is what he/she needs to solve their problem, address their issue, complete their task, etc.

And you know what they say happens when we assume. (For those of you who don’t know, ask someone older than you.)

Often the best response to a request is to first assure the requester that you can give them what they need and an approximation of how long it will take to get it done. By doing this, you’ve checked this off of their mental “to do” list and cleared the deck to ask them key questions that can demonstrate that you are a good and thinking account person.

And that is to ask them why they need the information and how they intend to use it.

Of course, the reason to do this is that they may not be asking for the right thing and/or there is something else that can better solve their problem. Now comes the tricky part.

You’ve got to ask these questions in a way that doesn’t make them feel challenged or foolish, if they asked for the wrong thing or didn’t know the right thing to ask for.

How do you do that? Here are some suggestions:

- “I want to learn as much as I can about your business (or what you do), so could you please tell me what you’re going to do with this information?”

- “I’m gonna get asked by “X” why I need this, what should I tell them?”

- “Are you going to use that information for “X” reason?

- Think of your own non-threatening, politically-correct way to ask, but do ask.

If it turns out that there is a better way to solve the problem, try to have the requester feel that he has been part of the solution. Making the requester a co-conspirator is always a good idea.

Net, net – given the choice, choose being right over being fast.

Question: We work at an agency with an outstanding creative reputation and a dedication to and focus on doing great creative work. What should the account manager’s role be in enhancing this?

Answer: There are a number of things that an account manager can do to achieve this.

Some of the more obvious ones are:

- Create a client environment that understands and is receptive to great creative work

- Share other Martin Agency creative work that you think is good and say why

- Do a competitive analysis on the creative work being done in the client’s category

- Send the client articles about creativity along with your commentary or point-of-view

- Send the client show reels from creative award shows

- Become a student of advertising. Know who’s doing great work. Know what new techniques are being used. Know who’s thinking “out of the box

- This will enable you to make more intelligent comments when you review work internally

- It will demonstrate to your creative team that you recognize and care about good work

- Become adept at selling great creative work to the client

- Determine how to ground the rationale for the work in reasons that are about the client’s business, not just because it’s cool work

- Find analogous situations in other categories that support the kind of work being recommended

- Try to “grease the skids” by pre-selling the work before the meeting and getting the client enthused and excited

- Identify anticipate client comments/objections before the meeting and prepare responses

(This might entail exposing the work to internal groups for reaction)

A couple more interesting suggestions:

- Take an advertising course in which you have to develop and present creative work

- See what it feels like to be in the creative team’s shoes

- Learn to anticipated possible reactions to the creative work

- Expand your cultural horizons

- Go to movies, plays, concerts and museums that you ordinarily would not attend to expand your creativity acceptance

- Buy your creative team a drink

- Listen to them talk about creative work, pick their brains, share your ideas. You’d be amazed how productive this can be

Question: How do you define the roles of Account Management versus Strategic Planning?

Answer: Before I answer this, a little historical perspective is in order.

When I first came into the advertising business (circa 1974), there was no such thing as account/strategic planning. And the development of creative strategy was clearly the purview of the account manager. The account manager was aided in this job by people in the agency’s Research Department.

Once the strategy was developed, it was reviewed with the client and modified as necessary. Once approved, it was given to the creatives (who were obligated to say that it was too complicated and had too much information to be communicated).

In the early 1980s, account planning was imported to the United States from London. Jane Newman (founder of Merkley Newman Harty) is generally credited with being a main force behind bringing planning to the U.S.

As originally conceived, planning represented “the voice of the consumer” in the conversation about how to talk to the consumer, and what to say to them.

Planning quickly became popular and initially most planners were researchers who changed their title to “planner.” As a result, there was a very quantitative orientation to planning. The early days of agency planning were more about whether an agency had a planning function than the benefits of having a planning function .

Over time, planning became more sophisticated and true planners (as opposed to researchers) became prevalent. The planning role evolved to a function of developing creative strategy and understanding the “brand” and its value/attributes.

And, as clients came to have a greater appreciation for understanding the value of their brand, the planner achieved an elevated role in the client’s eyes, and therefore within the agency.

The newly defined role of planners and their elevated importance to some clients had the de facto effect of diminishing the role of the account manager – in the industry at large and at The Martin Agency especially.

The truth is that the account manager’s role can be diminished, only if we let it. And if we let it, we are doing an important disservice to the client, to the agency and to ourselves.

The role of the account manager has indeed changed. And it is up to us to decide if we want that change to define our job as supervising the making of ads or taking on a bigger and I believe, more important role.

And that role, as you’ve heard me say many times, is to become the expert on the client’s business.

The more we know about the client’s business, their product/service, their distribution systems, their targets, their objectives, their politics, and how they go to market, etc., the more value we will have and the greater contribution we can make to the agency.

There are many benefits derived from knowing the client’s business, but the key ones are:

- It can ground our rationale for why a client should buy great creative work

- It can create client confidence in the agency, and therefore strengthen the relationship

- It can provide fertile knowledge to develop proactive initiatives that can generate incremental revenue for the agency

- It can make you an invaluable member of the client’s team and thereby increase the client’s loyalty to the agency and strengthen the security of the account

This is not to say that account managers should not be active participants in strategy development. They should. But it does say that there is a big, critical role that account managers can play, if they commit to it.

Question: One part of account management is being in the service business, and within that function you often play the role of facilitator to the client, to the creative teams and to our supervisors.

This doesn’t mean you have to be a “yes man.” And there will be times when you will disagree and need to push back.

So an important question becomes, “What are some of the ways to do this without creating frustration or alienation?”

Answer: The first part of the answer is that before you go about pushing back, make sure that you have communicated that you “get” the issue or problem. Many people will first assume that if you don’t agree with them, it’s because you didn’t understand them. You need to defuse that.

The second part of answering this question is that whatever you do, it must be done in as positive and constructive a way as possible. You need to keep the discussion focused on the content of the issue, not how you’re responding to it. No one ever wants to feel stupid or that they are not being listened to.

In terms of push back, obviously every issue is unique and the push back needs to be customized to fit the situation. But here are some generic things to consider:

- Ground your push back or disagreement in a business-related reason. Opinion is important, but if the client/creative/supervisor sees that it is the business that is driving your concern/disagreement, then it takes personal judgment and personality out of the equation and keeps it focused on the content, on which you as the account manager are an “expert.”

- Look for examples in analogous situations (in and out of the category) that support your case. Truth be told, most people tend to be risk averse, and demonstrating what others have done in similar situations may lessen the fear of doing something new or make them think twice about repeating a similar mistake.

- Have a recommended alternative solution. It’s easy to say, “I disagree,” but it’s a lot more difficult to develop, present and sell a different solution. It also is usually beneficial to enlist the support of a “co-conspirator” who is trusted by the person you are pushing back against.

- On a selective basis, sometimes it could make sense to bring in your supervisor or someone with greater clout to make your case. While this is not preferable, sometimes the “who says it” factor can be important, especially if the senior person is well-trusted or has a relationship with the person you are dealing with.

On a final note, be sensitive to when you need to give up the fight. If you are not going to win, you at least want to get to the point where you have not angered or alienated anyone, but you have gained great appreciation for having a point of view and not being afraid to stand up and support it.

Question: “You keep talking about the importance of being proactive with our clients. How should we do this?

Answer: Before we talk about how to be proactive, let’s make sure we understand why we should be proactive.

There are three primary reasons for account people (and the agency) to be proactive:

- Coming forth with creative ideas is one of the few things that the client either doesn’t have enough time to do or can’t do as well as the agency. (It’s one of the reasons they hire an agency.)

- Having value to the client as a source of ideas will make the client more reliant on us and more likely to be understanding of other agency shortcomings.

- There’s usually a good chance that agency ideas may lead to increased use of agency resources, which can lead to more revenue for the agency.

That said, it’s often hard to be proactive because it’s hard to find the time, it’s hard to get the client’s ear to listen to it and it’s hard to get the client to accept it.

Recognizing that each client, their relationship with the agency and their level of receptivity will be different, here are some ways to get started:

- Force yourself to set aside time dedicated to thinking about ideas for the client. The old cliché about “ask the busiest person you know to do something if you want it to get done,” is true. So pick one lunch hour per week or coffee time before work or a half hour before you leave work. Put it on your calendar and treat it like a mandatory meeting.

- You’re not in it alone. Solicit co-workers on your team or even people who don’t work on the account. Treat it like a mini-brainstorming session. It’s okay to make it fun, even outrageous.

- Focus on the client’s business. Never forget, the client walks around with a thought balloon over his head that says, “What’s in it for me?” First and foremost, the client wants to hear about ideas that will grow his business, be good for his brand and save him money. So you need to pretty much stay in those areas.

- Ideas can come from many places. Look at better ways to do what’s already being done. Look to other categories or industries and modify what they do, for your client. Have a quick 5-minute “what if” blue sky session. Don’t be afraid to be creative and out of the box and then reign ideas in.

- Make sure your idea is doable and defendable. Do enough homework to feel that the idea is implementable (which means practical, executable and affordable). The last thing we want is to diminish our credibility with the client by showing we don’t understand his business by suggesting an undoable idea.

- Grease the skids. Once you have an idea, make sure the client will be receptive to an idea coming from the agency in the area you’ve identified. If he says, yes, you probably have license to get additional information from him or even test-drive the idea by him.

- Present the idea in a smart and compelling manner. Pick a time when the client’s likely to be receptive. Make your presentation of the idea short, simple and clear. Be prepared to answer any and every question or objection the client may raise. Have a plan for implementation thought out, so that if the client likes the idea, you can answer the “what’s the next step?” question.

- If the client rejects the idea, make sure you get a clear and in-depth understanding of the reason for the rejection. Regroup and determine if the objection is overcomeable or addressable. If it is, try to get up to bat again.

- If the client buys the idea and it gets approved for implementation, make sure that your client, at a minimum, gets “co-conspirator” credit for the idea.

And, last, if a client buys your idea, I want to know about it so I can reward and reinforce this desired behavior from the account group.

Question: You keep reiterating the importance of account people getting into the client’s business. Why is this so important and how can we go about doing it?

Answer: At The Martin Agency as well as many agencies, there is a risk that account managers may fall into the trap of this line of thinking:

“If the creatives generate ideas, and the planners develop strategy, and the project managers handle administration, and the financial managers do billing and forecasting, then I guess the account person’s job is to oversee the creation and production of ads.”

That line of thinking may be true, but it is only partially correct. Overseeing the creative development and production process is an important and necessary part of the job, but it is only a part of the job.

The other major part of the job is to build a relationship with the client and to be as involved in and as knowledgeable about the client’s business as possible. (We’ll save building the client relationship for a future topic.)

This is important for a number of reasons:

●It can help sell great ideas and creative work. If our rationale for recommending something is rooted in why it is right for the client’s business, this will be a much more palatable rationale than because its “cool” advertising or our judgment that it’s good for the brand. (Remember, the client’s thought balloon always says, “What’s in it for me/my business.”)

●An understanding of the client’s business that is shared with the rest of the agency can provide fertile information for the agency to develop proactive ideas to help grow the client’s business. And at the end of the day, the reason that the client is at the agency is for ideas.

●An agency that truly knows a client’s business has real value to the client and the client/agency relationship. This value can help the agency get through the inevitable tough times when an agency error occurs or when we can’t crack the code on a creative assignment.

Although the goal is to get as far upstream in the client’s business as possible, that may only come in time, after you’ve established some initial client business involvement and understanding. Here are some ways/tips to begin to get into the client’s business:

- Periodically take the plant/factory/business tour.

- Read all client related trends, reports and industry/category periodicals

- Be knowledgeable about all client research, even if it’s not about advertising or the consumer

- Attend client business/industry update meetings

- Know how the client goes to market with his product or service

- Ask the client if you may attend his periodic staff meetings

- Do periodic field trips and store checks

- Meet and establish relationships with people at the client beyond the advertising/marketing departments

- Attend client industry trade shows and conventions

- Volunteer to be on internal client committees

- Spend time working in the client’s retail store

- Ask the client what you can do to increase your knowledge base of his business, and follow up on his suggestions

Undoubtedly, many of you are doing some of this, but I’m sure that no one has done it all. Invest the time to do it. You’ll make yourself and the agency valuable to the client. And that’s a great ROI on your time investment.

Question: Whether in day-to day business or on a shoot or just with an unexpected mistake, it seems there’s also a chance something can go terribly wrong on an account. Are there any guidelines on how to deal with a crisis?

Answer: While every crisis will undoubtedly have its own set of unique circumstances and variables, there are some common principles that can be applied.

First, do not panic or freak out, even if others around you do. Your team and the client are looking to you to see how serious the problem is, and to take control of the situation, and address the problem and restore normalcy.

And of course, it stands to reason that you are not going to do your best and clearest thinking on how to solve the problem if you are in panic mode. That said, you should also never dismiss the importance of a true crisis, because it will appear that either you don’t care or are not savvy enough to recognize the severity of the situation.

Second, gather all the facts, input and knowledge – chart the crisis – as quickly as you can. Speed is important to be able to take quick command of the situation. But it must be balanced with getting sufficient information to enable you to get a full understanding so you can make informed decision.

Once you land in a plan or action to address the crisis, balance it off knowledgeable and trusted constituencies. You may be responsible for “solving” the crisis, but you’re not in it alone. Share your proposed solution with your boss or your colleagues or someone whose opinion or acumen you respect. And don’t get hung up on your solution as the only one that can work. Be open to suggestions that can improve your thinking or even change it radically.

Before you make a final/formal solution recommendation, play some “war games”. Go through the exercise of thinking through things like:

- How will your recommendation be received by the client?

- Will this recommendation put the client in the best possible light?

- What is Plan B, if the recommendation doesn’t work?

- Are you prepared to review the other considered and rejected solutions and say why they’ve been rejected?

Whether your solution works or doesn’t work, learn from it. Write it up as a case history or file memo so others can learn from it.

Truth be told, you can’t learn how to handle a crisis by reading an e-mail about it. You have to experience it. I hope this helps to prepare you for the experience.

In 1974, on my first day in advertising at Doyle Dane Bernbach, the Management Supervisor (who is now Chairman of Chanel) on my account (S.O.S. Soap Pads) called me into his office. He said, “Here’s the most important thing you need to know about being an account executive – you can’t make points for doing your job well, you can only lose points for screwing up.”

It took me a while to get over the initial shock of this rather jolting introduction into account management. But, I came to realize that what he was saying was that it was my responsibility to make sure that everything ran smoothly so the client could be focused on the positive things that the agency was bringing to the relationship, and not get distracted by mistakes and errors.

I took the lesson to heart and re-defined his remarks to a focus on what I called “thinking defensively”. In a nutshell, what this means is to assume that anything could go wrong, and to have a back-up plan to deal with it.

Thinking defensively is really an attitude more than anything else. And in your role of account manager, it can manifest itself in innumerable ways. But here are a bunch of examples to illustrate what I mean.

• If you’re traveling to the client by plane, have a contingency travel plan in case the flight gets delayed /cancelled or the car doesn’t show up.

• Assume that the A/V equipment won’t work and the tape/CD will be faulty. Have back ups.

• Provide your team with the latest information about the client’s business category trends, competitive strategy just in case they get asked about it by the client in a meeting.

• Bring everything you might possibly need to a client meeting (past work, copies of the strategy, media plan, last conference reports, etc.) just in case it might be needed.

• Have everyone’s phone numbers (home, cell, office) handy in case you need to reach someone unexpectedly.

• Know how the client’s stock is doing and what’s going on in the category. It will always give you something to talk about with the client during conversation lulls or pregnant pauses.

• For internal meetings, make sure everyone attending knows the agenda, where the meeting is, who will be there and how long it will last.

I think you get the picture.

Question: When staffing accounts or going after new business, I’ve often heard about “horses for courses” or the need to “match” the client with the right people. What does this mean?

Answer: The short answer is that if you know what kind of person your client or prospect is, then you can do a better job of knowing how to sell to him and who should do the selling.

More specifically, many consultants feel that you can classify clients (and most people) into four basic types. And if you understand what type of person you’re dealing with, you can significantly increase your chance of success (selling an ad, establishing a relationship, staffing an account).

So here is a summary of the four basic types. (See if you can see yourself in one of them).

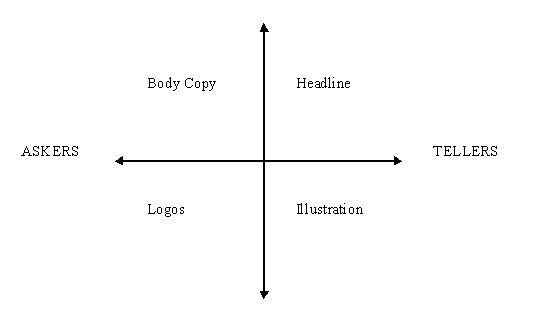

The metaphor here is that everyone essentially is like an element of a print ad – headline, body copy, logo or illustration.

The first thing to understand is that clients/people are divided into those who are task-oriented or people-oriented. And they are also divided into whether they are askers or tellers.

So the grid ends up looking like this:

TASK

|

PEOPLE

Here are the descriptions of the profiles:

Headliners – People who are headliners tend to have these characteristics:

- Business-like

- Interested in results

- Make snap decisions

- Risk takers

- Tend to ask first

- Care about efficiency

- Are well organized

- Dress appropriately

- Are leaders

- Are entrepreneurs

Body Copy – Bodycopy people have these tendencies

- Interested in process

- Business-like demeanor

- Very cautious

- Tend to ask first

- Occasional analysis-paralysis

- Use “to-do” lists

- Dress neatly, color-coordinated

- Like facts, details, examples

- Need and follow plans

Logos – Logos have these tendencies

- Interested in relationship

- Ask questions

- People-oriented

- Consensus builders

- Cautious

- Politically savvy

- Friendly and open

- Neat

- Are leaders

Illustrations – Illustrations tend to be:

- People-oriented

- Interested in first, newest, most, best

- Tend to act first

- Want to inspire and be inspired

- Impetuous

- Somewhat disorganized

- Pretty open with people

- Like to motivate and be motivated

- Somewhat flashy in dress

- Enthusiastic

- Poised and sociable

Now here are the two most important parts:

- If you can classify the type of person you are dealing with, you can package, position and organize your presentation, conversation, meeting, etc., to be as effective as it can be by being more relevant to the receivers.

- If you know what type of person you are, then you can know what to modify about yourself to be personally effective with whomever you are dealing.

One last note – research on this profiling suggests that Bodycopy people tend to marry Illustrations. And Headliners tend to marry Logos. Check it out with yourself and your mate. This may not be scientifically true, but anecdotally speaking, it’s true for this logo.

Question: The conventional wisdom in the advertising/marketing world is to never burn bridges. Is there ever a time when you can/should, and if so, how?

Answer: The conventional wisdom to not burn bridges is based on the accurate belief that the advertising/marketing community is so small and incestuous that it’s very possible that someone you have a negative experience with will cross your career path again. And you always need to be able to make that new situation become as positive as possible, without the old baggage rearing its ugly head.

That said, I believe that there are times that you should speak your mind, not just because it’s cathartic to do so, but because it’s the right thing to do.

Examples of this might include:

- Moral/Ethical Situations – If a client, boss or employee has acted in a way that has violated your (or the agency’s) code of ethics or moral standards of behavior, I believe you are in your right to let him know that you have found that behavior distasteful and unacceptable.

I think this is proper because we should not allow people to make us engage in or be a part of behavior we find ethically and morally repugnant. And since the likelihood of the person changing their behavior is minimal, we wouldn’t want to ever have to do business with them again anyway.

- Lack of Respect – Although we won’t always get people to work well together and respect each other as much as we’d like, the minimum we should expect is basic respect and civility. Our jobs are hard enough without adding in the variable of meanness or abrasiveness. When a working relationship that was abusive ends, I think it’s perfectly appropriate to let the person know how much more productive and fun and better the output would have been if their behavior had been better.

Of course, the tricky thing about telling someone off is to be able to do it in a way that is classy and doesn’t lower you to their standards, but is also totally impactful and effective.

So, here are a couple of suggestions:

- When you tell them off, do it alone, without an audience so they’re more likely to listen and less likely to grandstand.

- Do it in a way that is different than your usual demeanor to make sure you get their attention. If you’re usually quiet and polite, raise your voice. If you’re usually outgoing, be serious and focused.

- When they start to counter your statement or get defensive, don’t let them talk. It shouldn’t be a dialogue; it’s your time to vent. So tell them to save their breath, you don’t want to hear it. But tell them that the next time that they’re alone, to look in the mirror and see if they can tell the person in the mirror that what you said wasn’t true.”

And, it goes without saying that if you don’t think the person is even worth the time to tell off, then just walk away and think what we used to say when we were kids – “good riddance to bad rubbish!”

Question: Good account managers have to relate to and understand the needs of many different people. What are some ways to do this effectively?

Answer: The best account people are usually very compassionate or at least are perceived to be. If we loosely define compassion as an empathetic awareness of others – here are some things that can be done to demonstrate that.

- Listening vs. Hearing – Too often in conversation we only register the words that someone is saying to us while we wait for our turn to talk. That’s hearing. But listening is about paying attention to what is being said and thinking about what it means and how you respond or react to it. Repeating back to people what they said or re-phrasing it is a good way to acknowledge that you listened to them .

- Ask people what they think – We are often so focused on telling people what we think that we forget to get their opinion. This is particularly important in dealing with people who are not “type A” personalities or quiet people or people who are particularly thoughtful before they speak. Show people that you really care about what they have to say. It will go a long way.

- Pay attention to small details about people – Everyone has some level of ego. The fact that you remember something they said or something seemingly insignificant about them is both flattering and demonstrates that you are really paying attention to them. (By the way, did you know that John Adams has a really big sweet tooth?)

- Read a person’s “thought balloon” – Make the effort to play the game – “if I were in that guy’s shoes, what would I think?” Most people’s thought balloons are usually some variation on the theme of “what’s in it for me?” The account person who can figure that out and use it to position things to his advantage will always be ahead of the game.

A final thought – Bill Bernbach used to say that he carried a card around in his wallet and printed on the card was the phrase – “Maybe he’s right.” A smart sentiment from a really smart guy.

Question: One of the hardest parts of an account manager’s job is that you are constantly put in situations where you must deliver criticism. How can you do this without alienating someone or doing damage to the relationship?

Answer: First, you need to be absolutely positive that criticism is the most appropriate response from you to the person or situation. This means that you are confident that not only are you right, but that not criticizing will be detrimental to the situation.

That said, here are some “guidelines” I use when I need to offer criticism:

- Certainly the criticism should be offered as positively and constructively as possible. Point out how it could have been done better, rather than how poorly it was done.

- Be straightforward. It’s okay to point out the ramification of the actions/behavior that earned the criticism. The objective is for the person being criticized to know how they should have been done and why.

- Present the criticism directly to the person who needs to be criticized, not to his boss, colleagues or subordinates. Hearing criticism first-hand is not only more effective, it prevents the one being criticized from hearing it from a third party and inferring that it’s worse than it actually is.

- Present the criticism alone, one-on-one, not in front of anyone else. In addition to the obvious reason not to cause unnecessary embarrassment, a face-to-face conversation will lead to a more productive discussion and learning experience.

- Last and probably most important of all is the compassion with which you deliver the criticism. It’s important that you communicate that your objective is to improve the situation and for learning, not to demean or to vent. Talk to the person the way you would want to be talked to and don’t be afraid to let them know that you learned from constructive criticism, the very way that they are now.

And one final thing – avoid words like “jerk,” “idiot,” “knucklehead” and “if you do this once more, you’re fired.” Saying those things will undoubtedly hurt your credibility.

Question: Account people often are good either at managing up or managing down? Is it possible to be good at both?

Answer: No. Just kidding.

Obviously, the best account people are capable of doing both. But the truth is that it is hard to do and it is human nature to gravitate to the one you do more easily or are better at.

So here are a few suggestions that may help you do both kinds of managing well. Much of this may be self-evident, but the test lies in the consistent application of it in addition to the knowledge of it.

Managing Up

Many account people focus on managing up because they believe it is a short cut to faster career advancement. But good senior management at an agency can usually recognize people who can only “manage up, not down” and view the inability to do a good job of managing down with the team as a deficiency.

That notwithstanding, here are a few tips on managing up:

- Keep you boss/superior informed of all the key things he/she needs to know. A good rule of thumb is if the client called, how much information would he expect your boss to have, without feeling that he was micromanaging.

- Be proactive. Bring your boss ideas, thoughts, suggestions, etc. for your account, the agency or any other responsibilities he/she may have. If the boss likes an idea, offer to spearhead it.

- Talk about your boss positively to other people. Don’t make stuff up, but do stress positive things about him/her or what it’s like to work for him/her.

- When you bring your boss problems, always have a recommended solution(s). It may not be the perfect answer, but it takes the onus off him/her to solve it and gives him/her a starting point to build on.

Managing Down

Being a good team leader is an important skill that we tend not to pay enough attention to. In addition to it being important for leadership, it often has a big impact on morale and productivity. Here are some fundamental pointers:

- Communicate. Communicate. Communicate. The single biggest complaint people have about their bosses is that they don’t tell them what’s going on. This makes them feel insignificant and unimportant.

- Be firm and straightforward, but fair. It’s important to be direct with people to minimize miscommunication. Ambiguity to spare someone’s feelings may be an easy path to take, but it’s the wrong one. Constructive criticism is a good thing.

- Listen. Make the time to ask people what they think and then really think about what they’ve said. It’s great training for junior people and you’ll be delighted to get solutions you might not have thought of.

- As you do with your boss, ask your people to come to you with recommended solutions to problems. Again, it’s great training and part of the way to make them smarter/better account people.

- Be available and accessible. Let your people know that you have an open door policy and follow through on it. If they don’t come to you periodically, you should initiate a dialogue with them.

- Don’t micromanage. Give your people responsibility and autonomy. But let them know that you’re there as a “safety net” if they need you.

As you know, the “people” part of the advertising business and especially in account management is disproportionately high. Being great at your job is not only about the function and content of the job, but also very much about the how you get things done, how you communicate with people and how you work with people.

In this business, it’s incredibly rare to see a successful manager of accounts who is not also a successful manager of people.

Question: It seems we spend a lot of time revising systems, making process changes, inventing new ways to do things, etc., but all too often people revert back to their old behavior. Are there things that can be done to ensure that changed behavior stays changed?

Answer: It’s difficult enough to (pick your metaphor) “get a tiger to change his stripes,” or “teach an old dog new tricks.” But once you do, the bigger challenge is preventing people from reverting back to their old behavior, which is invariably easier and more comfortable.

So here are some suggestions that may maximize your chance of maintaining the new behavior:

- Make the person whose behavior needs to be changed a co-conspirator. When you discuss creating the behavior change with someone, guide the discussion so they feel some sense of ownership – that it’s their idea. It’s human nature to embrace our own ideas more strongly than others.

- Reinforce the new behavior. Make sure you overtly thank the people who have changed and let them know how much the new behavior is making a positive difference. It’s particularly important to do this at the time when they are exhibiting the new, desired behavior.

- Publicize the positive results from the new behavior. Let other people in the agency know what changes were done and how things are better/improved. And, do it throughout the agency to both junior and senior people.

- Make immediate course corrections when necessary. If the person reverts back to the old behavior, it’s important to discuss it and get back on track as quickly as possible. Obviously, this should be done in private and in a constructive manner.

As a department and an agency, we need to embrace change if we are going to grow and get better. Primarily we need to determine the right changes to make to achieve our goals. But equally important is to go beyond giving lip service to change and exhibit the behavior that makes the change real.

Question: We often look at having a good meeting as a metric of success. How can we maximize the number of good meetings that we have?

Answer: This is an important question. But, before answering it, remember that the end game is selling and producing ideas and work that grow the client’s business. Good meetings are a means to that end, not an end in themselves.

That said, the perfect “good meeting” follows the Chinese ritual of meetings, in that the meeting becomes a formality because much of the work has been done before the meeting. This is a result of a strong job of pre-selling.

There is no one right way to pre-sell, but here are some suggestions to help you along:

- Establish on-going, periodic phone calls with the client to catch up on things and talk about the business. Use these phone calls to do the pre-selling. A separate phone call to specifically pre-sell can sometimes get a wary reaction from a client.

- Agree with your creative team on what things they feel need to be pre-sold. They will have good input and insight into things that may be contentious. And you always want to keep the creatives in the loop so they are not “blind-sided” in the meeting.

- In pre-selling the client, don’t give away the actual content of the work. That needs to be saved for the meeting. For example, you might tell them that they are going to see some provocative testimonial work that you think is exactly right for the brand, without revealing the specifics of who the endorsers are or how it’s going to be done.

- The pre-selling should be positioned so as to whet the client’s appetite or make them eager to have the meeting so they can see what you’re talking about. For example, “We’re going to be showing you three campaigns. One of them is really ‘out of the box’ and I’m eager to see your reaction.” is a good way to pre-sell.

- Don’t oversell. It’s better to over-deliver than to over-promise. Overselling will bring your judgment into question with the client and usually results in a bad meeting.

Of course, the ultimate reality here is that we hope that we know our clients well enough to know when they need to be pre-sold and what way is most effective. But what’s clear is that effective pre-selling almost always makes for a positive meeting.

Question: What are the worst mistakes you can make as an account person?

Answer: Unfortunately, account managers are often evaluated like gymnastics or diving competitions. By that I mean your evaluation as an account person is too often determined by the mistakes you’ve made, rather than the value you contribute.

So, in an effort to avoid making big mistakes, here are some of the worst ones not to make:

Forgetting to deliver on a commitment to a client.

Whether it’s not returning a phone call, missing a meeting or not making a promised due date, all of these not only are rude, but send a signal to the client that his business is less important to you than other things. It is important that the client always feels that his business and related tasks are one of your top priorities.

Client thinks that you’re recommending an ad/campaign to win awards for the agency instead of being right for his business.

You need to make sure that the client feels that you “get” his business and what it needs. You don’t ever want him to question your priorities. If he does, you also risk having your credibility questioned.

Client catches you in a lie.

Don’t do this! Tell the truth because it’s the right thing to do (and easier to remember). If you lie or stretch the truth, only bad things can come of it. You make the client angry, you’ll lose credibility and you make the agency look bad.

Failure to keep your boss informed (about the good and the bad).

It’s not necessary that you tell your supervisor everything, but you should use your judgment to determine what he needs to know. You never want to have your boss be in the position of not knowing something he should know when he is talking to the client. It also enables your boss to be appropriately proactive.

“Dissing” the agency to the client.

Trying to get on the client’s good side by “dissing” the agency is a bad idea (even if the client is in agreement). If you do this, in the long-term the client is likely to form a negative opinion of you and the agency. Try to be a “glass half-full, not a glass half-empty” kind of account person.

Overpromising and underdelivering.

We always want to be in the position of exceeding the client’s expectations. If we oversell and set expectations unrealistically high, we look bad as an agency and start to erode our credibility with the client if we don’t live up to our promise.

Making your client look bad in front of his boss.

There is little or nothing to be gained by making your client look bad in front of his boss. It’s a good way to get the agency fired and even if that doesn’t happen, the client will never forget it. And the client’s boss is likely to disapprove of the behavior. Strive for the opposite. Make your client look like a hero in front of his boss. It’s likely to pay dividends in the long run.

Not being straightforward to the agency about how the client really feels.

Don’t fudge or soften how the client feels in order to spare people’s feelings at the agency. First, it wastes valuable time. Second, it can result in the wrong work being done. Third, you’ll lose credibility internally, especially with your creative teams.

Taking personal credit instead of crediting the agency teams.

Besides being wrong (and selfish), this behavior works against our objective of having the client believe that the agency is indispensable, not any one individual. While clients will always gravitate to specific people on the account, we need to make sure that they feel great about the entire agency so they do not get worried when we have to make a personnel change.

Bad-mouthing the client.

Irrespective of client behavior or decisions, it is never a good idea to dis the client back at the agency. It sets a bad example for junior people. It creates poor morale. And, if it ever gets back to the client, it runs the risk of disastrous repercussions.

Many years ago, on my first day in the agency business as an assistant AE, my management supervisor told me I couldn’t earn “points” by doing a good job, I could only lose points by messing up.”

While that helped me learn to think defensively, I don’t agree with the conclusion.

Account management can and should add real value to the client relationship and the quality of our product. Knowing what mistakes to avoid, can help maintain a strong and complete relationship with the client that can last a long time.

Question: There’s a lot of emphasis on training at The Martin Agency, but most of it is formalized or in seminar format. Where else should training take place?

Answer: The formalized training programs are designed to provide a solid base or foundation. But I really believe that the best training is on the job, coming from your boss or supervisor, who we hope will take his/her training responsibility seriously.

So for the supervisors/bosses, here are 10 tips on how to be a good trainer for the people who work for you.

Provide continuous, on-going feedback.

Training is a full-time job and should be done whenever the opportunity to train presents itself. Here’s an example – after a meeting, take the time to talk with the junior person to explain why you said what you did in the meeting or how what they said could have been done in a more effective way. Have this conversation right after the meeting, while it’s current, not three days later.

Expose junior people to areas beyond their responsibility.

Everyone likes to keep meetings small. But it’s a good practice to let junior people attend meetings they have nothing to do with and to let them sit there like a sponge and absorb. Someday they’ll be running that same meeting, and it would be great if their previous exposure enabled them to run it well.

Be straightforward, fun and fair.

You’re not doing junior people any favors by softening constructive criticism or dancing around an area where they need improvement. The goal is to make them better, smarter and more effective, not for you to be well-liked. In the end, there is a greater appreciation by junior people of truthful, direct conversation, than unclear, politically appropriate rhetoric.

Get to know your staff on a personal level.

Make the time to get out of the agency and go for a drink, lunch, coffee, whatever and get to know each other as people. I guarantee you that it will not only improve your working relationship, but it will enable you to get insight into the junior person that will help you be a more effective trainer of him/her.

Encourage and accept constructive criticism of your training techniques.

Accept the fact that your training style/technique may not be right for everyone. Be willing to customize your method of training to fit the individual to get the best results. The ability to do this may be a function of trial and error or figuring it out with the help of the junior person. But people learn differently and you need to adapt a “horses for courses” approach. (If you don’t get this metaphor, come see me.)

Set a good example because you’re actually training all the time.

Junior people look to their supervisors to see how they behave, communicate and handle problem situations. That’s part of the learning behavior. Often this may be more powerful than a seminar or training class. It’s important to be cognizant that you are an on-going role model to your staff.

Ask junior people about what training they feel they need.

Your assessment of the training needs of an individual is important, but it may not address areas that the individual feels insecure about but has kept hidden. You need to elicit that information from them by getting them to open up and admit where they need help in a way that is not embarrassing or demeaning to them. It’s important to follow this up with action, once you have the information.

Get people to bring you suggested solutions to problems.

We’ve touched on this before, but getting people to go through the behavior of thinking how to solve a problem can be an excellent training device. It’s real time, not theory and it can often be a good solution or be a catalyst that can lead to one.

Train people in how to train people.

Training is so important that you should try to make “how to train” part of your training of junior people. It is an important part of teaching them how to be a good manager and it’s a good reminder for you of what you should be doing to maintain your training practices.

Don’t be afraid to let people fail.

You will usually be able to do tasks better and more efficiently than junior people. But you need to selectively pick opportunities for them to handle things on their own. The key here is to let them know that they have authority and accountability on the project, but that you are there as a consultant and safety net, if needed.

Not everyone gravitates to training with the same level of enthusiasm. And certainly some of us are better trainers than others. But part of your job is to advance people’s careers or even groom your successor. So I urge you to take your training responsibility seriously. In the long run, it will be better for you, the trainee and the agency.

I have been using Friday Feedback as a forum to share tips, knowledge, experience, etc. about being the best account managers that we can be.

And to that end, I want to share with you the key points of a presentation entitled, “The Account Person of the Future” recently made by Jon Bond, CEO of Kirshenbaum Bond & Partners. Jon is a personal acquaintance of mine and also an excellent account guy.

In the “old” days (read 1960s – 1970s), the account manager’s role was that of a generalist. He got lots of different things done and he was the primary strategist, and he was in charge of the client relationship.

The 1980s saw the introduction of account/brand/strategic planning. And the role of the planner was to be the strategist, to write briefs, to manage research and to interact with and guide creatives. The net of this for the account manager was to lose his role as strategist.

The agency business has also seen the rise of project management, which replaced the conventional traffic system. Project management became true experts in managing logistics and work flow. And the best traffic managers (as we have here) wield significant power and influence, and are much more than mere executors. The net of this for the account person was to lose his role as the person who got things done.

Recently, we’ve witnessed more and more agencies promoting their expertise in the area of integrated marketing. This has resulted in budgets moving from advertising to direct marketing and interactive primarily for ROI reasons. This, in combination with the continued importance of PR and promotion, has meant that specialized account management skills have often undermined the need for general agency account people. Clients don’t want four account people in the same meeting, and they won’t pay for it. The net of this for the account manager is to lose his role as a generalist.

So, if the account manager has lost his roles as strategist, as the person who gets things done and as generalist, then all that is really left is the relationship. But if there’s no real job to do, how can there be a relationship?

Thus the question becomes, what should the account manager do?

Jon Bond’s opinion is that account managers should do less and think more.

There are many very tough issues facing the advertising industry today. The account person of the future should be thinking about how to address these issues. Here are a few examples:

- How should we deal with the integration of diverse marketing disciplines and new creative opportunities in our business and in the outside world?

- How can we measure the effectiveness of what we do in a world of insufficient tools?

- How can we justify our fees when everything we do is not quantifiable?

- How can we best manage client relationships in a world of flux?

On this last issue, Jon has some specific thoughts around what he calls Client CRM (Customer Relationship Management).

They are key “moments of truth” when it comes to client CRM. And great account people need to know how to manage client CRM because in today’s sometimes unstable environment, these “moments” can take on added significance.

Jon goes on to identify five key client CRM moments:

- The CMO leaves, or CEO leaves, followed by the CMO as soon as a new CEO enters.

- When you replace an old campaign with a new one or if an old campaign precedes current/new client management.

- A merger or acquisition, especially if your client is not in the power seat.

- Your campaign performs poorly – bad research results, is disliked internally or is perceived to fail in the marketplace.

- There are budget cuts, tied to poor business results.

When one of the key moments occurs, the key steps to take are:

- Spot it early

- Develop a plan to address it

- Take action early

- Get senior management involved (on both sides)

- Monitor the situation until the danger passes

While much of this may be self evident, there is a lot of sound advice here. And we all can benefit from paying attention to Jon Bond’s counsel.

The start of the New Year is a good time to take stock of our individual performances and relationships with our clients, and to make some “resolutions” and personal commitments as to how we can be even better account managers.

I’m not talking about the discussions we have in performance reviews or in an ownership team meeting. I’m talking about what you say to the person in the mirror to whom you can’t tell anything except the deepest truth.

So to that end, here are some tough questions to ask the person in the mirror:

- Have you sometimes said “yes” to a client request in an effort to be responsive, instead of determining the reason for the request?

- Have you ever not answered a client’s call because you were either busy with something else or you knew you could get back to him later, and it would be okay?

- Did the client ever have to call you a second (or third) time to repeat a request or check up on something?

- Have you initiated new ideas or better ways to do something than was currently being done?

- Have you made an effort to build a relationship with your client outside of business?

- Have you done anything to promote the agency to the client, beyond the work on your account?

- Does the client have all your telephone numbers (home, cell, etc.) in case he needs to reach you in an emergency (and vice versa)?

- Have you expanded your client knowledge base in terms of meeting new people or learning more about their business?

- Have you gone out of your way to integrate yourself into the client’s business – sales conferences, trade shows, trade publications, etc?

- Has the client been to the agency recently, to visit the creative “factory” or meet with agency management?

- Have you done a thorough job of evaluating the security of the account from competitive threats?

- Have you done a thorough job of evaluating cross-selling opportunities?

- Would the client perceive you as a “glass half-empty” or “glass half-full” kind of person?

- Does your client know what’s new at the agency – e.g. new business, new resources, new work?

These are a few questions to start. I’m sure that you can come up with many more.

But here’s the deal – I don’t want to know the answers. Tell the answers to the person in the mirror and make a commitment to him/her about the things you’ll do better in the next year. And, I’ll do the same to the person in my mirror.

There’s a Woody Allen quote that goes something like this – “80% of success in life is just showing up.”

If I may borrow from that thought, I believe that 80% of account management is about “showing up” to ensure quality work, grow the business, make money and build the relationship. But that leaves 20% unaccounted for.

The other 20% has to do with the instincts and antennae we use to foresee problems, predict trouble and get ahead of the curve on potential issues and concerns, to help us be proactive and defensive.

Acknowledging that some of this “skill set” is innate, there are still cognitive ways to get better at this.

Here are a couple of suggestions:

Pay attention to history

As the old saying goes – “Those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” Look at a client’s history on all levels – Does he pay his bills on time? How has he treated the agency? How is his taste in creative work? What is his tolerance for risk? All of these should be provide strong and clear clues for how he will behave with you and our agency.

The learning and information that comes from this kind of scrutiny can be immeasurably helpful in guiding our own behavior on things like – Should we take this client on? Should we make them pay up front? How should we staff the account? What’s the best way to sell our ideas and work to him?

And finally, at the risk of overusing clichés, be guided by the fact that most of the time, “if it looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck” then… well, you know the rest.

Don’t be afraid to seek counsel and guidance from those who have “been there”

There are many senior, experienced people at the agency, and many of you have mentors, who maintain a mental library of war stories, experiences and learning about clients and situational signs that are the harbingers of trouble.

Don’t be afraid, to ask other people who have had more and/or varied experience for their “take” on your client or a specific situation. It’s not a sign of weakness or incompetence to seek “outside counsel” when it comes to doing what’s necessary to avert disaster or to optimize a situation.

Follow your instincts with action

For most people, first instincts are usually pretty good. But problems can arise when that instinct is accepted as a low level irritant that you learn to live with, instead of a nagging feeling that can’t be ignored.

So when your antennae starts to twitch, telling you that things don’t feel “right” and you don’t like that way a client situation is shaping up, you need to commit to doing something about it.

Be nosy. Ask the client questions. Politely push for deeper answers than the ones that are politically correct. And if the diplomatic route doesn’t yield the answers you seek, don’t be afraid to have an “off the record” one-on-one conversation with the client. Most times, this will lead to flushing out the issue or at least having the client understand that you’re concerned.

Our desire to be successful account managers is rightly focused on results and performance – achieving goals, solving problems, etc. But let’s not lose sight of the fact that (and here’s my last cliché) “to be forewarned is to be forearmed”. And the best ways to be forewarned is to use our instincts and antennae.

I recently read an article about the lost art of mentoring in the agency business.

It served as a catalyst to remind you how important our Account Management mentoring program is and why we do it.

Why We Do It

First, we established the Mentoring Program for two reasons:

- I personally never had a sustained mentor throughout my career. As a result, I felt that I had to learn things primarily through experience and observation instead of benevolent counsel. Having a mentor offers an easier, better and more focused path.

- I truly believe that mentoring is a win-win-win situation. It helps the “mentee” become more proficient at his job, it is good for the mentor to “give back” by sharing wisdom and it helps the agency by developing the well-rounded, knowledgeable professionals we strive to be.

Why Mentoring Is Important

It’s a complement to training. The training we do is primarily about functional things – the “How To” stuff that teaches us about the “manufacturing” part of our job (making ads, writing decks, making presentations, understanding financials, etc.).

Mentoring is much more about coaching and counseling. It’s much more about the qualitative and subjective parts of our job – dealing with frustration, giving constructive criticism, handling disappointment, behaving with humility and compassion, etc.

It’s a responsibility we have to the agency. Part of what we need to give back to the agency is the development of people who can be part of and carry on the culture, so that future generations of people who work here can sustain the same mood, atmosphere and positive corporate citizenry that exist today.

Being a good mentor is a hard thing to do. It takes a serious commitment that takes precious time away from other important things – getting a job done, social life, family, etc.

It also takes an emotional commitment that is very much like parenting in its drive to help teach a child to be successful (even when the child/”mentee” doesn’t feel that he needs this guidance).

But mentoring is worth it and we’re committed to doing it, so here’s what I’d like you to do:

- If you are senior and aren’t someone’s mentor or if you’re junior and don’t have a mentor please come see me or Susan Foster to be assigned.

- Once the mentor relationship is established, go outside of the agency – for coffee, lunch, drinks and talk about the mentor relationship and what you want to get out of it.

- There are only three rules – the mentor relationship cannot be with someone you work with regularly, the relationship and its content are confidential, and you need to get together periodically (you define what this means) to do a “temperature check” to see how things are going.

I hope you take your commitment to mentoring seriously. It’s one of the many things that make The Martin Agency the special place that it is.

At a recent internal agency meeting, there was a lot of discussion/confusion about terminology that we use in our business every day…. specifically the differences in definition of mission, goals, objectives, strategy, execution and tactics.

Some of these terms are interchangeable. Some definitely are not. Some reflect the difference between WHAT and HOW. And some are similar, but are different because of scale/size.

Here’s how I see it:

MISSION

A mission is a very big, long-term end-result or achievement. There may be objectives, goals, strategies, executions and tactics all used to achieve the mission, but the mission is the biggest and most important thing to be accomplished.

Mission statements are usually the non-financial achievement that a CEO either develops for his company or is hired to achieve. The mission is a what versus a how, and is very similar to a vision statement in that it has a future orientation.

OBJECTIVES AND GOALS

I think that objectives and goals are interchangeable. They are the ends toward which effort and action are directed or coordinated. Although it is the aim or an end, it is not necessarily the final achievement. That’s the mission.

Objectives and goals are also whats, not hows, but they are smaller than a mission. There can be a number of objectives and goals to be achieved in order to achieve a mission, but there is usually only one mission.

STRATEGY

Strategy is how to achieve an objective, goal (or even a mission). It is a thoughtfully constructed plan or method or action that will be employed to achieve the result.

We often talk about people who are good strategists. These are people who excel at devising schemes and plans and courses of action to achieve the desired result.

As you advance in the ranks of account management you move from being more of a “doer” (execution, tactics) to being more of a “thinker” (developing strategies to achieve objectives and solve problems).

EXECUTION

Executions are what is done to deliver on or coordinate a strategy. They are definitely a what, not a how.

In our vernacular, they are the print ads, TV commercials and direct mail pieces, web sites, etc. that are developed from the creative brief/strategy statement.

Although execution is more about doing than thinking, it is still critical, as poor execution will prevent us from delivering on the strategy that will achieve our objective.

TACTICS

Tactics are devices or actions taken to achieve a larger purpose. They are also a what, not a how, but they are on a smaller scale than an execution.

When we say that someone is a good tactician, we mean he is good at making the smaller moves, gestures and acts that achieve a strategy. Many people often confuse tactics with strategy and also confuse tactics with execution, but there are differences, even if they are subtle.

Here’s an attempt at an example to demonstrate the use of these terms.

Mission – To make the XYZ company largest seller of premium candy

Objectives/Goals – Achieve share of market leadership in the premium candy segment.

– Be known as the most expensive candy, but worth it.

Strategy – Convince consumers that XYZ candy is the best premium candy by associating with high-end people and entities.

Execution – TV and Print ads using wealthy celebrity endorsers.

Tactics – Sample XYZ candy in high-end department stores

– Put XYZ candy on the pillows of beds in high-end hotels

I hope this clarifies things. That was my objective.

A couple of people outside of Account Management suggested that it might be a good idea to have a refresher for senior people and a new communication to new account people about the components of effectively running a meeting.

While much of the following may be common sense practice, we all often get off track because individuals have hidden agendas that emerge in a meeting or assertive individuals (sometimes clients) try to take over the meeting.

So here are my “Ten Commandments for an Effective Meeting”

1. Unless agreed to otherwise, the account person should be the leader of the meeting, which means having the responsibility for agenda, attendees, time, duration, refreshments and managing the outcome of the meeting.

2. Be compulsively organized. Have an agenda done. Make sure everyone knows when and where the meeting is. Have any materials/equipment that might be needed for the meeting, in the room in advance of the meeting. Make sure the room is big enough. Schedule the meeting to last long enough to cover the agenda. Think through everything you might need or want before the meeting and make sure it all gets done.

3. Customize your agenda. The more formal the meeting, the more necessary it is to have a specific agenda (usually written) that should be reviewed at the start of the meeting. Less formal meetings can use an oral review of agenda. It may often make sense to review the agenda with the key attendees prior to the meeting, to ensure that what they want covered will be addressed.

4. Choose attendees appropriately. By and large, meeting attendance should be limited only to people who have a contribution to make or a need to know the content and outcome of the meeting. This, of course, should be balanced against training opportunities to expose junior people to new areas and learning situations.

5. As leader of the meeting, the account person should manage and orchestrate the meeting. This would include, reviewing the agenda, setting the time parameters, outlining expectations and outcomes and summarizing meeting deliverables. The account person should make sure that everyone is in agreement with all of that and be given the opportunity to amend it or add to it.

6. Manage the tone and tempo of the meeting. Keep the meeting on topic. Try not to let it turn into a negative, gripe session. Keep the comments constructive, positive and moving towards solutions or actions that will lead to solutions. Keep the pace of the meeting moving. Know when to move from one topic to another. Summarize the discussion of each topic before you move on to the next one.

7. Show compassion for the attendees. Solicit opinions and viewpoints of attendees. Be cognizant that not everyone is a type-A personality. Some people need to listen and absorb before they speak. But give everyone an opportunity to voice their point of view. Do not allow constant interruptions or more than one discussion to go on at the same time. Make sure that people are courteous and polite to each other, even if they are in disagreement.

8. End the meeting with a summary of agreements and action steps. Make sure that everyone is on the same page as to what these are. And be very clear on who has responsibility for each action and what the timing/due dates of those actions are. Try to never leave a meeting with unresolved issues or unanswered questions.

9. Determine the appropriate post-meeting follow up. Formal client meetings will require a conference report. Some meetings may only need an informal re-cap. First-time meetings often require a need for a “thank you, great to meet you” note. And sometimes it may need a face-to-face check-in with people to make sure that they are clear on what they are supposed to do.

10. Remember that good meetings are important, but they are not the end game. They are the means to the end. Having a series of great meetings that everyone feels good about may make for good interim reports, but as the account person, you are responsible for coordinating the actions that get results.

Meetings are a necessary part of our business. Use them strategically to build team morale, to develop good internal and external relations or even as a training tool.

But as the account person, always remember – it’s your meeting.

The recent on-going transition of the Wal-Mart account into the agency reflects a situation that we often face in the advertising business, especially on the Account Management side. Specifically, what do you do when you have an overwhelming workload and not enough time or resources to get it all done. While it is unusual to face this situation in Wal-Mart proportions, it is often reflected in the uneven nature of the work flow on our accounts.

So here are some tips, most of which should be common sense.

- Once you have a handle on all of the work/projects that need to be done, sort them by importance and urgency as follows

- Focus your efforts primarily on high importance and high urgency tasks, as these are likely to have the biggest impact on the business and more of the client’s attention.

- Invest time on the high importance, low urgency projects, as they will likely become more urgent over time.

- Knock off a low importance, high urgency task every once in a while to get them out of the way.

- Ignore the low importance, low urgency tasks. They’ll likely go away on their own, anyway.

- If you determine that you’re in real trouble, raise your hand. You will not have failed if you have to go to your supervisor or manager and ask for help. And it will result in two good outcomes – you’ll get the help you need to get the work done and you won’t stress yourself out.

- Be aware that if you’re not able to complete all the work within the hours that we’ve budgeted, then we either have to hire more people or amend the contract with the client, or both.

- Above all, try to stay cool, calm and collected, even if you feel emotionally stressed out. We don’t want the client to feel that we’re not in control. And don’t forget, junior people are looking to you as a role model and example of how they should behave under stress.

The uneven nature of the work flow will often create overloads and stress periods. And as the old saying goes, “when you’re up to your ass in alligators, it’s hard to remember that your objective was to drain the swamp”. But as good account managers we need to put a premium on keeping a clear, logical head and remaining unflappable at all times.