The Erotic History of Advertising

The Erotic History of Advertising

Aromatic Aphrodisiacs: Fragrance

By Tom Reichert

“Hello?”

“You snore.”

“And you steal all the covers. What time did you leave?”

“Six-thirty. You looked like a toppled Greek statue lying there. Only some tourist had swiped your fig leaf. I was tempted to wake you up.”

“I miss you already.”

“You’re going to miss something else. Have you looked in the bathroom yet?”

“Why?”

“I took your bottle of Paco Rabanne cologne.”

“What on earth are you going to do with it…give it to a secret lover you’ve got stashed away in San Francisco?”

“I’m going to take some and rub it on my body when I go to bed tonight. And then I’m going to remember every little thing about you…and last night.”

“Do you know what your voice is doing to me?

“You aren’t the only one with imagination. I’ve got to go; they’re calling my flight. I’ll be back Tuesday. Can I bring you anything?”

“My Paco Rabanne. And a fig leaf.”

Paco Rabanne – A cologne for men. What is remembered is up to you.

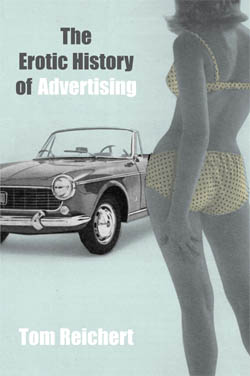

Not convinced about the power of product placement? Paco Rabanne had no hesitations. The company discovered a way to inventively insert its own product-Paco Rabanne cologne-into a series of sexually laden tête-à-têtes. The dialogue belonged to a two-page spread revealing the inside of an artist’s flat (see fig. 9.1). Against the far wall a man sits up in bed, sheets to his hips, talking on the phone; an empty bottle of wine sits near the foot of his bed. The dialogue flows down the page on the other side of the ad.

Additional vignettes include a lonely writer in Pawgansett, a musician with a towel wrapped around his waist promising the caller another bedtime story, and a man on his boat making arrangements for a rendezvous. All flirted with their lovers over the telephone, and all plots revolved around a missing (or empty) bottle of Paco Rabanne.

The ads created a mini-sensation when they first appeared in the early-1980s. Readers had fun guessing what the other person looked like. Some even speculated about the caller’s gender-notice that the text is ambiguous, and there is that reference about “a secret lover…stashed away in San Francisco.” An academic study even investigated another Paco Rabanne ad to see how readers interpreted the motive of a female caller-was she a slut, in control, out of control, rich?

Sexual content in fragrance advertising is manifest in the usual ways: as models showing skin-chests and breasts, open shirts, tight-fitting clothing-and as dalliances involving touching, kissing, embracing, and voyeurism. These outward forms of sexual content are often woven into the explicit and implicit sexual promises discussed in Chapter 1: promises to make the wearer more sexually attractive, more likely to engage in sexual behavior, or simply “feel” more sexy for one’s own enjoyment.

The Paco Rabanne campaign didn’t contain nudity (much anyway), and it didn’t come right out and say, “This is what attracts her to you…or you to him.” But, like most fragrance advertising, the campaign did create a sensual mood, and moods are essential in fragrance advertising. “A fragrance doesn’t do anything. It doesn’t stop wetness. It doesn’t unclog your drain. To create a fantasy for the consumer is what fragrance is all about. And sex and romance are a big part of where people’s fantasies tend to run,” confessed Robert Green, vice president of advertising for Calvin Klein Cosmetics, to the New York Times.

One thing is certain: fragrance marketers play to people’s fantasies. A study in 1970 conducted by marketing analyst Suzanne Grayson revealed that sex was the central positioning strategy for 49 percent of the fragrances on the market. The second highest positioning strategy was outdoor/sports at 14 percent. In Grayson’s analysis, sexual themes ranged from raw sex to romance with the fragrance positioned as an aphrodisiac-an aromatic potion that evoked intimate feelings or provoked behavioral expression of those feelings. According to Richard Roth, an account executive for Prince Matchabelli, “Fragrance will always be sold with a desirability motif.” Roth’s prediction, made in 1980, proved accurate as desirability, attraction, and passion remained central themes in fragrance positioning through today. What did change, however, was the content and expression of the desire motif over time. For one, as the Paco Rabanne repartee demonstrates, women became equal partners in “the chase.”

Fragrance Advertising in the 1970s

The 1970s were viewed by some in the industry as a cooling off period, when blatant sexual come-ons-at least those targeted to women-came to be considered passé and in bad taste. Some industry experts predicted that as sex roles evolved, with women entering the workforce and pushing for equality, sexual appeals casting the woman as a sex object would decrease. Grayson’s study seemed to confirm these observations. While sex was the largest positioning strategy in 1970, by 1979 only 28 percent of fragrances used a sex-only strategy. Sex was still present in many ads, but it was combined with other strategies such as youth, status, sports, and fantasy, which of course could have a sexual underlying theme. The tenor of women’s fragrances changed from the theme of turning on men to turning on the self-of being in control and self-sufficient.

Two women’s fragrances, described in more detail in the following sections, exemplify this transition. Introduced in 1975, Aviance used the “desirable quarry” approach. The perfume’s message was: use this to turn on your men. Effective then, this type of approach was soon deemed as “not what women respond to.” By the end of the 1970s, appeals could still contain sex but those with women in control would prove most effective. Fantasy was deemed a exemplary approach: “In fantasy, a lover may be part of the picture, but he is not needed, isn’t integral. Most importantly, sexual fantasy represents the woman in control.” Chanel’s 1979 ad featured fantasy as well as a subtle sexual reference.

Targeting men? That’s a different story. Use whatever strategy works, and Jovan chose one that was brazenly sexual. Its ads made outright promises, or pledges, rather, about the sexual outcomes of using its colognes. The campaign proved very successful, leaving one to wonder if men will ever learn.

Aviance’s “Night” Campaign

Despite having a scent described by its own marketing director as “not that appealing,” Aviance perfume proved to be a smash for Prince Matchabelli. Mark Larcy, now the president of Parfums de Coeur, was the marketing director who put together a successful campaign designed to play to the insecurities and desires of stay-at-home wives in the mid-1970s. The “I’m going to have an Aviance night” campaign sought to “…reassure the traditional housewife that she was still alluring, still exciting, and still able to be wild and carefree with the man she loved,” wrote brand historian Anita Louise Coryell.

Debuting in September 1975, the campaign’s original commercial was built around the proverbial “lingerie-clad wife meets husband at the door” motif. The spot features a woman transforming herself from housewife to lover-with Aviance as the latchkey. The housewife “throws off her unsightly cleaning clothes, including her bandana wrapped around her hair, dons an alluring negligee, coifs her hair, puts on makeup, and sprays herself with Aviance. She greets her husband at the door with a fetching look, and he gives her the once-over. His eyes light up with approval,” wrote Coryell. Anticipation may have been on his mind. The spot’s jingle was especially catchy: “I’ve been sweet and I’ve been good, I’ve had a whole full day of motherhood, but I’m gonna have an Aviance night.”

Short-lived, the spots ran intermittently for four months in 1975. The print campaign consisted of a four-color, full-page shot of the husband leaning against the doorway, as seen through the bare legs of what is assumed to be his horizontally positioned wife (see fig. 9.2). She raises the knee of one of her legs to create a triangle that frames the scene.

The ads were designed to appeal to an emergent segment of the population-women who were staying home in an era when more feminist-minded women were entering the workforce. In-depth research commissioned by Larcy found what he described as, “The stay-at-homes visualized their husbands at work with voluptuous, liberated women.” In addition, research revealed that women used fragrance to assist with role transformation-it helped them move from mother and wife to a sexual partner, or what Larcy described as “their better sexy shelf.” Aviance was positioned as the fragrance that would assist in that transformation.

Despite subsequent criticism about the way the woman in the ad is objectified-whose only worth to her man is as a sexual plaything-women played an integral role in the campaign’s development. The research effort was led by a female sociologist who was able to tap not only the insecurities, but the predilections and aspirations of women in the focus groups. In addition, the ad was produced by the female-agency Advertising to Women, the only agency to understand the product’s positioning, said Larcy. Even the jingle was created by the agency’s president, Lois Geraci Ernst.

In spite of its unappealing “strong, slightly musky scent,” the spot resonated with women. Aviance sold over $7 million its first year and the ad was selected by Advertising Age as one of the best commercials in 1975. In the 1980s, sexualized women would continue to be a mainstay in fragrance advertising, but women were just as apt to objectify as to be objectified.

Chanel “Share[s] the Fantasy”

Chanel first aired its “Share the Fantasy” or “Pool” commercial in 1979. The sensual spot was conspicuous for its lack of sexual explicitness and bold propositions. Showcasing a woman’s fantasy, the commercial was praised for requiring viewers to fill in the “missing images.”

Selling for over $250 an ounce, Chanel No. 5 has been one of the world’s top-selling perfumes since its introduction on May 5, 1921. An enduring symbol of French designer Coco Chanel’s influence, the package has remained virtually unchanged since she first tested the fragrance in the vial labeled “Chanel No. 5.” According to brand researcher William Baue, the 1979 commercial for Chanel No. 5 “became a defining moment for the French fragrance and company’s fashion advertising.” The campaign was part of an overall effort to boost the House of Chanel image, which had diminished after Coco Chanel’s death in 1971. The campaign was an important step for the company to help it reposition itself for the future.

The commercial began with dramatic yet sensuous retro music, and a shot of the enticing blue water in a swimming pool. A woman, facing away from the camera, lies on her back at the edge of the pool. The shadow of an airplane passes over her, followed by a woman’s European-accented voice-over, “I am made of blue sky and golden light, and I will feel this way forever.” A tall, dark man in a black Euro-style swimsuit dives in the water from the other side of the pool. Swimming underwater, he rises up in front of her-then disappears. “Share the Fantasy” was the tagline for the commercial, but only in the American version. It wasn’t needed in France where Chanel’s brand identity is at icon status.

Directed by Ridley Scott, a British film director whose later credits include Alien, Blade Runner, and Thelma & Louise, the spot was produced in-house under the guidance of Chanel’s longtime artistic director Jacques Helleu. A beautiful spot with rich colors, it was truly an indulgent yet tranquil fantasy-sure to lower heart rates in its brief 30 seconds.

The spot’s lack of carnality and blatant sexual referents diverged from other fragrance advertising at the time. “Focusing on fantasy allowed Chanel to harness the power of sexuality without crossing the border into distaste,” observed brand researcher William Baue. The subtle approach was a wise strategy considering that the target audience was older women: “Our advertising is sexy, but never sleazy. If anything, we tend to pull back, rather than go too far, which is opposite of the rest of the business,” remarked Lyle Saunders, a Chanel executive, to Adweek. “Pool” was one of five spots produced for the long-running campaign; the spot ran from 1979 until at least 1985, perhaps longer. Although the company doesn’t release its sales figures, Chanel ratcheted up its prestigious image, and Chanel No. 5 never lost its position as one of the top best-selling perfumes in the world.

Jovan’s Advice: “Get Your Share”…of?

Jovan, Inc., a small fragrance marketer, spiced up consumer advertising and the fragrance industry in the mid-1970s. Executives at the company used blatant sex appeals to boldly introduce a line of musk-oil-based colognes and perfumes. Headlines proclaimed, “Sex Appeal. Now you don’t have to be born with it,” and “Drop for drop, Jovan Musk Oil has brought more men and women together than any other fragrance in history.” The approach earned the company and its three executives accolades, and sales soared from $1.5 million in 1971 to $77 million by 1978. Eleven years after it was founded, a British conglomerate bought Jovan for $85 million. With no previous experience in the fragrance industry, Jovan’s founding executives implemented a sexual marketing strategy that proved to be a very smart venture.

Bernard Mitchell and Berry Shipp were looking to get into a new line of business in 1968 when they founded Jovan with a mink bath oil product. The company’s name was chosen for two reasons: Jovan sounded French, and the name was similar to the company’s two primary competitors, Revlon and Avon. Richard Meyer, a Chicago ad executive, soon joined Jovan to write the ads and creatively manage the fragrance campaigns. Meyer eventually became president of the company.

The company’s success was linked to its Jovan Musk Oil, introduced in 1972. Musk, a synthetic version of an animal pheromone, was marketed for its ability to enhance sexual attraction-though musk’s magnetism is debatable. The product’s genesis was happenstance. Shipp was passing through Greenwich Village when he saw lines of young people buying small bottles of full-strength musk from street venders. Shipp carried the idea back to Jovan, and soon the company was producing a fragrance based largely on musk. Until then, musk had been used only in small amounts as a fragrance additive.

The company’s success was tied to several factors, one of which was its sexual marketing strategy. All promotional activities appeared to position the fragrance as a sexual entrée. For example, consumers were told that Jovan products would help them attract members of the opposite sex, and increase their odds for steamy liaisons. Many Jovan ads contained the subtle argument that people were having sex, and if the reader wasn’t satisfied with his or her “share,” Jovan could be of service. Sex and intimacy were the prizes, and Jovan was positioned as the purchase that helped consumers achieve those ends. Consider a Jovan Musk Oil headline in 1977: “In a world filled with blatant propositions, brash overtures, bold invitations, and brazen proposals…Get your share.”

A 1975 retail ad for Jovan Sex Appeal aftershave/cologne for men, contained the headline, “Sex Appeal for Sale. Come in and get yours.” The tagline read, “Jovan Sex Appeal. Now you don’t have to be born with it.” The only image in the ad, besides the headline, was an illustration of boxed Jovan bottles. The packaging was unique because it was the ad’s copy. The anti-packaging, this brown bag approach, fit the spirit of the ’70s. What did Sex Appeal smell like? Just read the box: “[a] provocative blend of exotic spices and smoldering woods interwoven with animal musk tones.” The description begs the question, what exactly is an animal musk tone? And what species were they referring to-dog or wild jungle beast? It didn’t matter, consumers were buying Jovan by the truckload.

The Fragrance Foundation also liked the ads. In 1975 it voted Jovan’s Musk Oil promotion the “most exciting and creative national advertisement campaign.” Jovan’s CEO, Bernie Mitchell, also earned an industry award. He was voted “the year’s most outstanding person.”

Often, the packaged fragrance was the only illustration. These ads contained attention getting headlines relying on double entendre, references to sex, and explicit promises. Copy in the ads served to elaborate on the suggestive reference in the headline. Consider a 1977 ad appearing in Jet magazine. It contained the headline, “And, it’s legal.” The copy went on to read: The provocative scent that instinctively calms and yet arouses your basic animal desires. And hers. …A no nonsense scent all your own. With lingering powers that will last as long as you do. And then some. …It may not put more women into your life. But it will probably put more life into your women. Because it’s the message lotion. Get it on!

Other ads contained images of nudity and sexually suggestive behavior. For example, another full-page ad appearing in Jet contained a small image of an apparently naked Black couple in a passionate embrace. He’s kissing her neck. Her head is tilted back and her eyes are closed, seemingly in rapture. The headline read, “Drop for drop, Jovan Musk Oil has brought more men and women together than any other fragrance in history.”

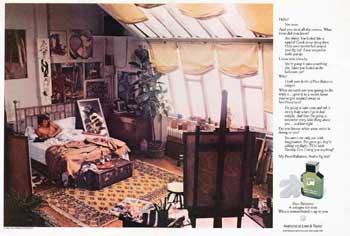

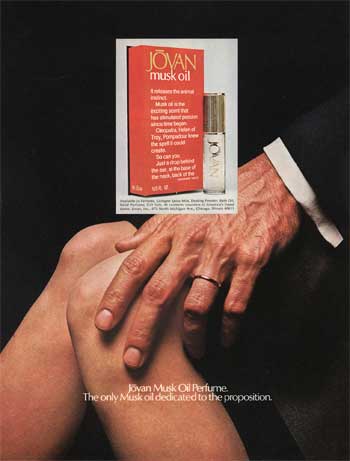

A seductive ad targeted to women ran in issues of magazines in 1976 (see fig. 9.3). The headline read, “Jovan Musk Oil Perfume. The only Musk oil dedicated to the proposition.” The image was an extreme close-up shot of a man’s hand lightly resting on a woman’s knee. The man is wearing a wedding ring, but who knows for sure if it’s his wife’s leg he’s touching-it was the ’70s after all. The packaging on the box reads: “It releases the animal instinct. Musk oil is the exciting scent that has stimulated passion since time began. Cleopatra, Helen of Troy, Pompadour knew the spell it could create. So can you.” Similarly styled ads promoted men’s cologne. For example, an ad scheduled to run in Jet contained Black models in a similarly posed shot.

The headline in a 1976 ad, targeted toward women, contained a blatant double entendre typical of Jovan ads, “Someone you know wants it” (see fig. 9.4). Another ad for a different fragrance targeted toward women, Belle de Jovan perfume, contained an image reminiscent of a 1930s romantic appeal. In the hazy image, a man is kissing a woman’s neck. The headline reads, “Introducing Belle de Jovan Perfume. Open. Apply. Experience. Savor. Whisper. Touch. Caress. Stroke. Kiss. . .” There is little doubt about the lustful allusion in this ad. As a call to action, the ad’s tagline reads, “Wear it for him. Before someone else does.”

A 1977 Jovan ad designed to appeal to men read: “11 great Jovan aftershave/colognes. If one doesn’t get her, another will.” The scene evokes thoughts of a singles’ bar. The man is sitting at a bar with a drink, looking at the viewer. A smiling woman closes her eyes as she whiffs his cologne. The obvious meaning is that men will attract women if they wear one (the correct one, mind you) of Jovan’s colognes.

Jovan carried its sexual expression one step further when it sponsored a limerick contest in 1979. The company invested $500,000 in television and magazine advertising to promote the contest. Readers submitted new last lines for limericks published in the ads. Winners were eligible for cash prizes and trips to Club Med. In the ad, the limerick was scrawled on a wall in the men’s room. Other scrawl in the ad attempted to make the scene believable. For instance, there were hearts with initials in them, a Kilroy-esque symbol, and a phone number for “Arlene.” The limerick read as follows:

There was a young man named McNair, Whose cologne did defile the air. Women with him were brusk, Until he tried Jovan Musk, And now he gets more than his share.

“More” was bold and underlined. A limerick aimed at women told of a boring young maiden who “pleasantly found of the action around, She now gets her share and much more.” These limericks helped to reinforce Jovan’s “get some” strategy.

Until Jovan’s brazen advertising approach, fragrance ads had been mysterious and subtle about the seductive powers of their perfumes. According to an Advertising Age writer, “Perhaps it is because the company’s blatant claims about enhancing the sensual characteristics of a woman’s basic animal instincts exploit what the more decorous fragrance marketers have only been hinting at for years.” Another writer observed that Jovan had ignored the “mystic marketing approach beloved by established fragrance houses”-much to its own success.

Jovan’s success was also tied to is distribution strategy. Unlike most advertised fragrances, Jovan mass marketed its products like packaged goods instead of upscale, image-conscious products. Compared to most colognes and perfumes, Jovan was very competitively priced. For example, smaller bottles were priced at $1.50 and displayed near the checkout at mass merchandisers, drugstores, and department stores. In 1976 for example, Jovan was available in over 22,000 outlets. Using a convenience goods marketing technique (extensive distribution and low price point), Jovan ramped up sales. One ad headline unabashedly proclaimed, “Sex Appeal by Jovan. Now at Walgreens.”

Jovan also created demand for a “wardrobe” of fragrances. Instead of purchasing one Jovan fragrance, consumers were encouraged to use different fragrances throughout the day. Depending on your activities (or goals), there were lighter scents for work and play. In 1977, for example, there were eleven product lines-scents, as Jovan preferred to refer to them-for men. A line of “light colognes” for women was promoted in an interesting ad. A woman is shown sitting between two men who are obviously interested in her. All of them are wearing sports attire (e.g. tennis shorts, tank tops) and she’s signaling “time out” with her hands. “Sometimes you’d rather keep it light,” read the headline. What was the message? If you want to smell nice but keep the boys at bay, wear a lighter musk. In 1981 Jovan introduced Andron (for men and women), a pheromone-based, fragrance. True to form, Andron’s pheromone mixture was touted as a signal for sex.

As previously mentioned, an innovative technique used by Jovan was to print sales copy directly on the box. This approach was referred to as the “talking package” because copy on the box described the contents. For example, a magazine ad for Jovan’s Sex Appeal in 1975 featured images of a teal box with silver and white lettering. Aside from the headline, “Now you don’t have to be born with it,” the ad’s copy was what was printed on the packaging. “This provocative, stimulating blend of rare spices and herbs was created by man for the sole purpose of attracting woman. At will.” The copy also proclaims that men can never have enough “sex appeal.” This particular ad ran in Viva, Cosmopolitan, and Oui. Ads for Sex Appeal for Women fragrance appeared in Harper’s Bazaar, Mademoiselle, Glamour, Essence, and People.

Jovan is the story of a sexual positioning strategy that paid off handsomely. In Jovan’s advertising, packaging, and promotions, sex was always at the core. True, perceptions did exist at the time that musk, Jovan’s primary ingredient, was a sexual attractant, but Meyer and Jovan’s agencies exploited the belief for all it was worth. Unlike other fragrance ads up to that time, Jovan’s advertising contained unabashed sexual claims that Jovan users would become sexual magnets.

More important, Jovan’s appeals resonated with consumers. In 1976, Jovan was third in market share for men’s fragrances and tenth for women’s lines. Although market share for men’s fragrances was a fifth of the market for women’s fragrances, Jovan exploited a male market that was just beginning to take interest in personal care. As a result of its success, Jovan was bought for $85 million by British conglomerate Beecham. With over 97 percent of the purchase price going to Jovan’s three top executives, it’s fair to say that they “got their share.”

Fragrance Advertising in the 1980s

If there was a theme in 1980s fragrance advertising, it was that women and men were equals in the sexual pursuit. Forbes writer Joshua Levine commented in 1990, “Advertisements today frequently picture women as sexual aggressors or at least equal sparring partners, rather than available sex objects.” He could have been describing any number of fragrance ads targeted to both women and men. Perhaps it was the Paco Rabanne ads described earlier, in which the women are just as deft as the men at trading playful one-liners.

Revlon’s Charlie created a stir with a subtle gender-bending pat on the backside in 1987. Successful since its introduction in 1973, writer Robert Crooke described the Charlie campaign as “geared to a theme of energy and female self-sufficiency that borders on brazenness.” Shelley Hack, soon to join Charlie’s Angels, was the original model. The brazenness was put into action when a Charlie model reached down and gave her male colleague a pat that lives in infamy. Was the gesture sexual or merely playful? According to Mal MacDougall, the man who wrote the ad, “It was meant as an asexual gesture, the same kind of thing a quarterback does to a lineman.” Not everyone was convinced; the New York Times refused to run the ads, saying they were sexist and in poor taste.

Women’s newfound sexual assertiveness was evident in many ads at the time. A 1985 ad for Anne Klein perfume shows a couple disrobing in a sequence of 12 snapshots. The woman begins the action by pulling off the man’s tie-no headline for the ad was necessary. A woman pins a man against the side of a giant fragrance bottle in a Coty Musk cologne ad. Pulling his shirt off, she presses up against him, a leg thrust between his: “It must be the Musk.” In “The Joy of Sax” ad for Saxon aftershave, a woman is shown stroking a man’s face: “Your partner will respond to the difference.”

Another trend influenced the look of fragrance advertising in the 1980s. Referring to the influence of AIDS, Adweek’s Dottie Enrico made the following observation in 1987: “Today we’re seeing plenty of sex in ads, but much of it is being couched in the more cautious context of obviously monogamous relationships.” Enrico was referring to a dampening of unabashed sexual interaction in advertising. Reflecting the country’s mood, the headline for a Coty Emeraude perfume ad read: “I love only one man. I wear only one fragrance.”

Revlon struck the right balance with Charlie, but hit resistance with its Intimate perfume television spot in 1987. Hot (and cold) and steamy, the spot contained what some referred to as a 9 1/2 Weeks-inspired ice cube scene. In the ad, a man sensually runs an ice cube down a woman’s cheek and neck. The ad had to be reworked before it was allowed to run on network television. “It’s chilling-both literally and figuratively,” remarked market researcher Judith Langer, of Langer and Associates. “I think it went too far for a lot of people.” Although the couple was “partnered,” the ad was deemed too risqué at a time when, as Levine noted, “fear of AIDS has given overt sexual imagery menacing overtones.” The print version of the campaign contained the headline, “An Intimate Party,” and tagline, “The Uninhibited Fragrance.” Revlon’s Intimate wasn’t the only fragrance spot that had to be reworked. Networks refused to clear a broadcast version of the Paco Rabanne dialogue ad until the male model donned a wedding ring. “I think we’re seeing less of the swinging single in advertising because of the current health situation,” advertising executive Lynne Seid told Adweek.

Despite the dampening of erotic imagery, nudity-especially in Calvin Klein fragrance ads-set new boundaries. Although Obsession was not introduced until 1985, Calvin Klein campaigns dominated fragrance advertising in the 1980s; not in sheer number, but in tone.

We are grateful to Tom Reichert and Prometheus Books for granting aef.com permission to post this excerpt.

Tom Reichert

Copyright © 2003. All rights reserved.